The Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) states that federal funds should be used for effective instruction and intervention programs. A new website, evidenceforessa.org, has been created to provide districts with an easy way to check a program’s effectiveness. The website was produced by the Center for Research and Reform in Education (CRRE) at Johns Hopkins University School of Education in collaboration with technical and stakeholder advisory groups. The website states that “it provides a free, authoritative, user-centered database to help anyone – school, district, or state leaders, teachers, parents, or concerned citizens – easily find programs and practices that align to the ESSA evidence standards and meet their local needs.” The ratings are ranked from strong (having the most evidence aligned with the ESSA standards) to moderate or promising, and down to the ones that have no statistical evidence to support their use.

The Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) states that federal funds should be used for effective instruction and intervention programs. A new website, evidenceforessa.org, has been created to provide districts with an easy way to check a program’s effectiveness. The website was produced by the Center for Research and Reform in Education (CRRE) at Johns Hopkins University School of Education in collaboration with technical and stakeholder advisory groups. The website states that “it provides a free, authoritative, user-centered database to help anyone – school, district, or state leaders, teachers, parents, or concerned citizens – easily find programs and practices that align to the ESSA evidence standards and meet their local needs.” The ratings are ranked from strong (having the most evidence aligned with the ESSA standards) to moderate or promising, and down to the ones that have no statistical evidence to support their use.

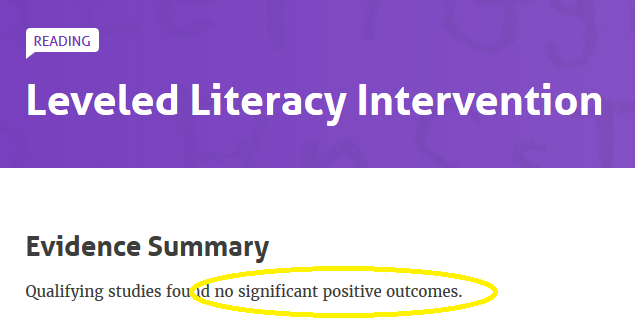

Interestingly, if one were to use the website and look up Leveled Literacy Intervention (LLI) by Fountas and Pinnell, an intervention program used in most districts across Long Island for children with reading difficulties, maybe even in most districts across NYS, one would see these words under the evidence summary, “Qualifying studies found no significant positive outcomes.” How could this be? Isn’t this the “go-to” program of choice?

Having worked with many children who were given the LLI intervention, I am not surprised that this program was found to have no significant positive outcomes. Why? The books used for this program, particularly the lower level ones, have repetitive or predictable text, which basically teach children to look at pictures and remember sight words. Since such students likely have not made the connection between letter and sound correspondences, they tend to use whole word memorization as their default strategy when reading. The LLI books reinforce this contextual guessing strategy. Rather than encouraging children to read “left to right and all through the word,” the LLI books are sending children mixed messages about how to read. It is not unusual to see children’s eyes jumping around to search for meaning while using “word solving” strategies which do not rely on the alphabetic code of letters matching to sounds throughout the written word.

Decodable text, on the other hand, builds a strong phonics understanding by slowly introducing the alphabetic code from simple to complex letter patterns. It is designed to be a teaching tool to reinforce phonics from the bottom up. Developing strong foundational skills in phonemic awareness and phonics should be an early reading priority for the fragile reader.

Even schools that claim to offer phonics instruction in addition to the LLI do not understand how damaging this can be. One would think that the more strategies provided the better, and that variety accounts for a true “balanced literacy” program. The problem occurs when children are being taught phonics for a small portion of the day, but then practice reading using every other strategy but phonics! This is equivalent to learning steps to salsa dance and then thinking these steps would be useful in doing the waltz. Just because one learned phonics in an isolated lesson does not mean one will be able to transfer the knowledge to uncontrolled text. Faced with words beyond their ability to decode, children will naturally guess or use pictorial cueing to “read” the words. Children need lots and lots of practice learning letter and sound correspondences using cumulative, decodable readers.

Older children with adequate decoding skills might be helped somewhat with the LLI program if their reading issue is generally poor comprehension. But more often than not, the struggling reader gets stuck at one of LLI’s letter levels, and isn’t able to move beyond it. Children are relegated to lower level groups and continue to read books that are below grade level. They become unchallenged and unmotivated to read while their literacy skills stagnate. Children are also told they must choose books within their level when picking books of their choice. So even if they really want to read books that are above their reading level, they are guided to a book bin for lower level readers.

So, what does this mean for the majority of children receiving reading intervention services in school? The Leveled Literacy Intervention program will probably not help them to reach grade level expectations.

Faith Borkowsky, Owner and Lead Educational Consultant of High Five Literacy and Academic Coaching, is a Certified Wilson Dyslexia Practitioner, is Orton-Gillingham trained, and has extensive training and experience in a number of other research-based, peer-reviewed programs that have produced positive gains for students with dyslexia, auditory processing disorder, ADD/ADHD, and a host of learning difficulties. Her book, Reading Intervention Behind School Walls: Why Your Child Continues to Struggle, is available on Amazon. See information on her book and an interview with Ms. Borkowsky at: https://highfiveliteracy.com/book/

11 Comments. Leave new

[…] Children usually receive more of the same ill-conceived teaching methods when pulled out of the classroom for extra help. Most schools use Leveled Literacy Intervention (LLI) instead of a Structured Literacy approach. […]

Yes, children will receive what the teacher knows, not what the student needs.

All children can learn; however not all children learn in the same way. I have used both methods, both have produced good readers. Teachers must dig deep, and know their students . You find out what they know and start from that point.

It’s not the program. It’s the lack of training for those using the program. Also what is happening in the classroom. Classroom teacher needs regular time to meet with teacher of LLI to share expectations.

Hi Marilyn,

You make some good points. Implementation has a lot to do with the success of any program, and there needs to be a collaborative effort between the classroom teacher and interventionist. With that said, beginner readers need a solid foundation in phonemic awareness and phonics. Although a good teacher can supplement, it is usually not intensive enough for the child who struggles in these areas.

I am very interested in your article and the website listed above. I also agree that LLI has the issues discussed. However, when I went to the website that the information came from, LLI is said to have a strong impact on reading, with an affect size of 0.13. The screen shot that appears in the article is not the same look that I see on the website. Could you please give more information about where this information on LLI came from? There seems to be a discrepancy.

Hi Lindsey. There were no positive statistical outcomes on the ESSA website at the time this was written. Very interesting – see this article. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4712689/

Thank you! I 100% agree with this article.

I’m not seeing the statement of “no significant positive outcomes” and am instead seeing F&P Intervention being rated as strong. I also see Reading Recovery rated as strong. I’m concerned and confused. Please let me know what I;m missing.

Thanks!

Yes, it is confusing! When I wrote that blog, the information was different. Please see the follow-up blog, “Intervention: Can We Trust Evidence for ESSA?”

I think the way the Evidence for ESSA site displays the data is confusing. The rating of Strong, Moderate, etc refers to the strength of the evidence, not the strength of the impact of the program. Strong means there was at least one well designed experimental study with a statistically significant effect on improving reading outcomes. The FAQs on the site explain more about this. The effect size has to do with the percent chance someone who went through the program would have a higher score than someone who did not. Regarding, LLI mentioned above, an effect size of .13 is considered small. Put another way, it means that there is only about a 54% chance that a person who went through LLI would have a higher score than someone who had not.