Guest Blogger Harriett Janetos, Reading Specialist

Author, From Sound to Summary: Braiding the Reading Rope to Make Words Make Sense

Speech-to-Print first spoke to me when I was co-teaching a first-grade class and stumbled upon Why Our Children Can’t Read and What We Can Do About It: A Scientific Revolution in Reading by cognitive psychologist Diane McGuinness. focuses on taking the 44 (+ or -) phonemes of the English language as the starting point for reading instruction and teaching the most common spelling variations for these phonemes: speech-to-print. This was my second year in a job share, teaching two days a week. The previous year I had only taught one Friday a week during which I was responsible for staggered reading in the morning (and afternoon) with ten students; followed by an extended read-aloud and process writing with the whole class; and then teaching art to all the first grade classes during the second half of the day.

I mention this teaching assignment because my transition from high school English teacher into an elementary school classroom, armed with a teaching credential and a master’s in writing instruction but no training in teaching beginning reading, landed me in known territory. On ‘Fun Friday’ I guided students through story writing, transforming them into budding authors and illustrators who eventually created a bound story (if stapled construction paper counts as binding!).

At this time, five years before getting my reading specialist credential, I had no idea that the invented spelling my first graders were engaging in was making them better readers. This was two decades before Timothy Shanahan’s blog “Explicit Spelling Instruction or Invented Spelling?” where he stresses that “one of the major reasons for engaging kids in spelling invention is to induce them to closely think about the phonemic structure of words and the relationship of those phonemes with letters.”

My students were taking their speech, spreading it across their fingers to compose a sentence, and sounding out their words to transfer that speech-to-print onto lined paper that had grand gaps to guide their letter formation. Their handwriting may have been strained, but their ideas were interesting and imaginative, as grand as the writing paper. Although their sentence mechanics were far less mature than those of my high school students, through support, the mainstay of good writing was on display: elaboration, elaboration, elaboration.

Timothy Shanahan goes on to comment on the connection between invented spelling and speech-to-print:

Not surprisingly, many phonics advocates prefer ‘speech-to-print.’ Part of the reason for this may be that speech-to-print–getting kids to go from sounds to letters–provides greater opportunity for kids to develop phonemic sensitivity . . . Nascent readers benefit from analyzing the speech stream and attempting to map letters to those sounds.

Dykstra’s Decision-Making

Although there is no definitive research with head-to-head studies comparing speech-to-print (S2P) with print-to-speech (P2P), I’ve been hedging my bets and leading my lessons with oral language for reasons like that provided by Timothy Shanahan: taking advantage of the logical connection between spoken language and the letters that represent it in writing. Steve Dykstra cautions that a lack of “bullseye” evidence for a particular instructional method shouldn’t automatically rule out that method if it can be part of making reasonable decisions that we believe will benefit our students. He says:

We are not required to be right; we are required to have ‘right’ reasons that we can explain to other professionals . . . Know where the science ends and your best judgment begins.

Since I know where the science ends when it comes to speech-to-print, my goal is to explain my best judgment regarding reading instruction by providing the reasons underpinning the choices I make. These reasons are right right now, subject to change if and when the science tells me I need to. They include a simplified lesson structure that constrains me from overteaching linguistic components since my reference point is always the sounds of the language and their implications for instruction: Letters are pictures of sounds; there is variation in the code (one sound can have several spelling variations with one or more letters); and there is overlap (the same spelling can represent different sounds).

In brief, I choose to begin my introduction to a new spelling pattern via speech-to-print to emphasize the oral language that my students are (for the most part) already familiar with, and I use their speech as a springboard into reading. This is why dictation figures prominently in my lessons as children hear words, repeat those words, say the phonemes in those words as they write the graphemes, and then say the words as they read them aloud–reading instruction that sails through the speech stream.

First, a Prototype

However, it wasn’t nostalgia for my first-graders’ composition know-how that turned me into a reading teacher five years later whose lessons led with oral language–though I was both intrigued with and impressed by how they were able to make their spoken words appear in print, as Jeannine Herron explains in her book Making Speech Visible: Constructing Words Can Help Children Organize Their Brains for Skillful Reading:

This book proposes a simple, but fundamental, change in the way children are introduced to reading. It explains how this change could result in more efficient reading pathways in the brain. The switch is as simple as this: children need to construct words themselves before they try to read someone else’s words. They need to SEE how the alphabet code represents what they SAY. Reversing the order of instruction in this way-writing as a route to reading-could help prevent the reading difficulties that turn many children away from the joy of reading.

It was, to be honest, the simplicity inherent in the speech-to-print approach that inspired me because it saved me from sorting through the details (and detritus) of overly-complex teacher’s manuals, searching for quality lessons to stitch together for my reading students. In other words, it prevented me from overteaching phonics. By the time I started working with elementary school reading intervention groups, I had read all of Diane McGuinness’s academic books and appreciated their straightforward, researched-informed recommendations.

In fact, when–post-reading specialist credential–I suddenly found myself for the first time in charge of teaching reading and writing to a kindergarten class, I ignored the teacher’s manuals altogether and just used the student materials and Diane McGuinness’s prototype from Early Reading Instruction: What Science Really Tells Us about How to Teach Reading (2004) to guide me–the former providing a scope and sequence embedded in the decodable books, the latter, the roadmap for the scaffolds and structured lessons to teach the graphemes representing the phonemes. This was half-day kindergarten, so no time for fluff–just the stuff that mattered. Anita Archer would have been proud.

According to Diane McGuinness, there are a few basic elements of a successful reading/spelling program for teaching the English alphabetic code, which I’ve listed below. In the parentheses following these elements, I’ve noted one or more researchers/educators whose publications over the past two decades have aligned in various ways (if not completely) with these recommendations. Note in the first bullet point that what Diane McGuinness is referring to when she says no sight words are high-frequency words that are memorized as a whole–not words that become recognized by sight after they have been orthographically mapped by connecting phonology, orthography, and semantics (sounds, letters, and meaning)–which include all words, not just those that are high-frequency. (Bolded words were originally italicized in the book for emphasis.)

- No sight words (except high-frequency words with rare spellings). (Linnea Ehri)

- No letter names. (Stanislas Dehaene)

- Sound-to-print’ orientation. Phonemes, not letters, are the basis for the code. (Richard Gentry and Gene Ouellette)

- Teach phonemes only and no other sound units. (Susan Brady)

- Begin with an artificial transparent alphabet or basic code: a one-to-one correspondence between 40 phonemes and their most common spelling. (David Share)

- Teach children to identify and sequence sounds in real words by segmenting and blending, using letters. (Susan Brady)

- Teach children how to write each letter. Integrate writing into every lesson. (Steve Graham)

- Link writing, spelling and reading to ensure children learn that the alphabet is a code, and that the code works in both directions: encoding/decoding. (Linnea Ehri)

- Spelling should be accurate or, at a minimum, phonetically accurate (all things within reason). (Gene Ouellette and Monique Sénéchal)

- Lessons should move on to include the advanced spelling code. (Louisa Moats)

Diane McGuinness refers to teaching the basic and advanced code, but how much of the advanced code to teach is debatable. In their 2009 study, “Real books vs reading schemes: a new perspective from instructional psychology,” Solity and Vousden analyzed the frequency of grapheme-phoneme correspondences (GPCs) in children’s literature, finding that knowledge of the 64 most frequent GPCs enables readers to decode approximately 75% of monosyllabic words encountered in texts. Speech-to-print advocates are mindful of exposing students to spelling variations of a sound, but there is no demand for mastery of these spelling patterns before moving on to working with a different sound and its various spellings. And certainly, exposing students to less common patterns (ough, aigh, gn) is different from actively teaching those patterns.

However, although it was this simplicity related to the logic of the code (as McGuinness refers to it) that got me hooked on speech-to-print, it was my evolving awareness of other speech-related concepts that kept me coming back: specifically child-directed speech, the lexical restructuring model, and–as I had already experienced with my first-graders–invented spelling. Without effort, I had stumbled upon a range of reading-related fundamentals with a range of research that supported integrating speech into my reading instruction as often as possible. And whenever that research was inconclusive, my best judgment drew its own conclusions for classroom instruction, always mindful that this instruction needed to be both effective and efficient.

In brief, I concluded that since Invented spelling is widely known, well-researched, and commonly used, it was a practice I should adopt. When I discovered child-directed speech in a TED Talk by Anne Fernald, where she explains the importance of receptive vocabulary (most recently emphasized in the book Strive for Five, which encourages teachers to engage in conversations with students that involve at least five exchanges), I became convinced that talking to my students in as many different situations as possible really matters. Although the Lexical Restructuring Model reflects a hypothesis that is far less studied and far less discussed than the other two concepts, it does have some research support that suggests speech-based activities to promote vocabulary development have value because, in part, of the byproduct of this development: phonemic awareness.

Before exploring each of these, it’s useful to take a quick look at what it means to find ourselves in a speech-to-print classroom and how leading with spoken language lands us in a productive place, a field of phonemes and graphemes that creates a speech-infused environment for all of our literacy lessons.

Speaking, Seeing–and Seeking Common Ground

Lately, the reading world has engaged in a minor skirmish tangentially related to the reading wars–an acceptance by many of structured literacy over balanced literacy but a bit of head-butting over how to approach phonics. We need to make sense of the seemingly senseless difference between the two approaches–speech-to-print vs. print-to-speech–to account for our day-to-day decisions and to accelerate a rapprochement amongst reading teachers for the benefit of the students we serve. If a speech-to-print approach can accelerate reading proficiency through simplified lessons that don’t overteach phonics, this is to be desired since there are so many educational goals competing for our attention in the classroom. Once we’ve established that a phonics program is effective, we don’t stop there. We need to ask whether it accomplishes its goals in the most efficient way possible to prevent opportunity costs from accruing.

Here’s how, two decades after I taught writing to first graders, Jeannine Herron explains what was happening in my students’ brains, which helps me understand the utility and efficiency of a speech-to-print approach, an approach that emphasizes working with the existing language structure students bring with them into the classroom.

From Print-to-Speech and Speech-to-Print: Mapping Early Literacy:

- If children segment a familiar word like mat in order to spell it, the speech sounds get linked to concrete letters that are used to make that spoken word visible.

- The visible letters they assemble or write can help them to retain the memory of pronouncing that sound.

- The physical act of writing also adds more motor learning to these multi-modal links. This process is called encoding.

- As they learn their letter-sounds, children begin to choose the letters and spell out the words by themselves. They are turning words they can say into words they can see . . They begin to figure out that they can write any word they can say.

- Brain research shows that early reading requires development of neural pathways linking speech to new learning about print. Memorizing the visual appearance of words does not require the same participation of speech. More efficient brain pathways develop as children master PA, phonics, the alphabet code, and word knowledge in order to encode and decode meaningful text.

In a recent blog about the difference between oral language and written language, Claude Goldenberg discusses Stanislas Dehaene’s research into how the spoken word, once accessed through hearing, is now accessed through vision during reading. Dehaene says:

A massive bundle of connections link . . . visual areas . . . with . . . regions involved in phonological coding . . . As a result, we gain the ability to access the spoken language system through vision.

Then, in “Two sides of a single coin – speech-to-print, print-to-speech – let’s not devalue the currency”, Anna Desjardins explains the importance of this circuitry as follows:

The implication is that to optimise the establishment of this circuitry during reading instruction, children should be systematically taught how letters map to speech sounds and vice versa, and should work on these connections in two directions: from print-to-speech, and from speech-to-print. There is no need for these two terms to be pitted against each other, when in fact, they are two sides of a single coin.

Lastly, In the video Who Moved My Socks–Why Speech-to-print Instruction Matters, Jan Wasowicz explains that since our brains are already organized around the speech that we’ve heard and the sounds we have voiced since learning to speak, there is a logic to beginning with speech rather than print, which echoes Diane McGuinness’s adherence to linguistic phonics in order to abide by the logic of the code.

Logic aside, there is an integration of skills inherent in my speech-to-print activities that have a logic of their own. It makes sense when I am in my Dykstra-inspired decision-making mode to engage as many brain modalities as possible–especially speaking–during reading instruction, in addition to integrating as many literacy components as possible. Therefore, I choose to begin with representing speech with print rather than the other way around in order to facilitate this integration.

Speech Takes Center Stage: The Speech-to-Print Advantage

In fact, this may be the salient point that separates me from my print-to-speech colleagues: simply starting my reading lessons with spoken language. And since both P2S and S2P can be effective approaches if they devote lessons to encoding and decoding, it’s this starting point that often sets us apart, in addition–depending on the instructor–to making sure vocalization is loud and clear and ever-present in all word-related lessons.

As previously noted, there are no head-to-head studies comparing the two approaches. And the truth is that just as there are a variety of P2S programs with varying degrees of effectiveness, the same can be said for S2P, so we would need to compare programs specifically rather than orientations generally if we wanted to drill down on which approach has added value for our students.

However, we do have research into the language processes involved in reading acquisition which can provide instructional considerations by proxy. In The Language Literacy Network infographic, which builds on Scarborough’s Reading Rope through the inclusion of Language Expression in addition to Language Comprehension, the speech-to-print advantage is explained as providing higher quality mental representations as well as a more complete transfer of learning from encoding to decoding. In a 2008 article these higher quality mental representations are explained by David Share:

Even when spelling highly familiar words, the writer is obliged to retrieve the elements of the visual form of the word whereas reading only requires recognition (Perfetti, 1997). When spelling, furthermore, the writer must process each and every letter. In reading, on the other hand, the orthographic representation may be less than fully specified yet sufficient for word identification, particularly when encountered in meaningful context (Holmes & Carruthers, 1998) . . . We predicted not only that spelling a novel word would lead to significant orthographic learning but also that spelling would actually be superior to reading (i.e. decoding). In addition, we expected this advantage to be most clearly evident in the case of spelling production compared with spelling recognition.

Gene Ouellette offers another advantage to providing encoding experiences:

The sophistication of a child’s invented spelling tells us about the level of development of the brain’s reading circuit–it’s like brain imaging in action . . . Not only does invented spelling reflect the child’s speech perception and knowledge of print, it actually reflects changes that are happening in the developing brain.

Finally, in a 2014 study Linnea Ehri completes this emphasis on the importance of speech:

Vocabulary learning is facilitated when spellings accompany pronunciations and meanings of new words to activate orthographic mapping. Teaching students the strategy of pronouncing novel words aloud as they read text silently activates orthographic mapping and helps them build their vocabularies. Because spelling-sound connections are retained in memory, they impact the processing of phonological constituents and phonological memory for words.

Students carry with them into all of their word-work the phonological luggage from their reading lessons, transporting the priming for phonemes they’ve received, expressed and made visible through the production of graphemes on the page, voiced as they write them down. It is important to emphasize that print-to-speech methods that are aligned to research do not neglect encoding and can be equally effective. However, when not done effectively, these lessons are often conducted in silence, with students completing activities where they are sorting and matching words without voicing the graphemes or pronouncing the words that contain them. Speech-to-print promotes pronunciation at all turns, not just while reading aloud. My classroom motto: MAKE SOME NOISE.

In Sync with Sounds and Letters

The authors of Teaching Phonemic Awareness in 2024: A Guide for Educators make some recommendations related to phonemic awareness (PA) that are problematic when it comes to the importance of integrating PA with phonics in order to facilitate recognition of what sounds look like in print. I’ve bolded what I see as problem areas followed by my comments. These comments rest on the premise that we want our instruction to be as efficient as possible to improve reading outcomes, not just phonemic awareness outcomes.

The authors write:

When deciding whether to use letters to teach phonemic awareness, educators may want to consider the following.

- When teaching phonemic awareness with letters, each practice word must be spellable by all children in the group. Avoid spoken words with letter patterns that have yet to be learned.

Note: If we integrate PA with phonics, we can use segmenting and blending activities to teach new spelling patterns representing sounds. The activities themselves provide the practice in order for these “letter patterns” to be “learned” so they eventually become spellable by all children.

- Some spoken words will be difficult for novice readers to represent with letters. For example, the same long A sound is spelled with different letters in “cake,” “paid,” “may,” “steak,” “hey,” and “weigh.”

Note: That’s the whole point! We are teaching spelling patterns and the sounds they represent. Dictated word chains with pay/paid/raid/rain/ray/may/main practice both PA and phonics together, especially when we are asking students to say the sound (phoneme) as they write the spelling pattern (grapheme).

- If using letters in a phonemic-awareness-style task, teachers must decide whether the child who segments “paid” into /p/ /a/ /d/ and chooses the letters p-a-d has given a correct answer or an incorrect answer, when the goal of the activity is to build phonemic awareness.

Note: This is a great example of the importance of efficiency. It is more efficient to combine PA with phonics so that students have the opportunity to learn and practice spelling patterns. The goal of the activity should be to help students become better readers, and building phonemic awareness is a byproduct–not the goal–of the activity.

- When letters are used in phonemic-awareness-style tasks, letter identification errors and letter reversals can interfere with learning the phonemic awareness task.

Note: Once again, is the goal to learn a phonemic awareness task or to become a better reader? In discussing their 2024 meta-analysis on The Teaching Literacy Podcast, Erbeli and Rice emphasize that both PA with and without letters improved phonemic awareness, but it was PA with letters that improved spelling and reading.

- If letters are always used during phonemic awareness instruction, then phonemic awareness instruction becomes indistinguishable from spelling regular words.

Note: Why is this such a bad thing if using letters during phonemic awareness instruction leads to better reading outcomes?

- One of the main reasons to begin phonemic awareness instruction is to facilitate learning for students who are struggling with learning phonics and spelling words as they sound. Such students are likely to know fewer letter-sound correspondences, so using letters instead of tokens in phonemic awareness tasks can limit the number of items for practice.

Note: If students are shown the letters on the board and/or have letter tiles to manipulate, they can learn letter-sound correspondences as they practice PA.

- Using letters can confuse the interpretation of student errors. If a student responds incorrectly to a phonemic task using letters, it is difficult to know whether the error is due to poor phonemic awareness or inadequate letter-sound knowledge.

Note: If a child makes/writes the word ‘brain’ as ‘bain’, it’s a PA problem. If they make/write the word ‘brain’ as ‘brayn’, it’s a phonics problem. And if they make/write it as ‘bayn’, it’s both.

The Interplay between Child-Directed Speech, Invented Spelling, and the Lexical Restructuring Model in the Speech-to-Print Approach

As previously stated, I’ve come to realize that the instructional sequence that I call speech-to-print rests upon the relationship between three literacy processes, which provide a rationale for my instruction beyond the arguments made in the books by Diane McGuinness and others. These arguments emphasize the simplicity of working with the 44 phonemes and their representations in speech by taking the familiarity of the spoken word and making that speech visible through print. This fundamental relationship between speech and print is important, and this importance is emphasized through these three literacy processes:

- Child-Directed Speech: In her TED Talk Why Talking to Little Kids Matters, Anne Fernald explains her research with infants 18-24 months that reveals the importance of child-directed speech to develop a child’s vocabulary and increase processing speed, two factors that affect future reading ability.

- Invented Spelling: In order to express themselves in writing, children draw upon their active vocabulary to write by turning the words they say into words they see. Research by Gene Ouellette and Monique Sénéchal emphasizes that invented spelling “influenced subsequent conventional spelling along with phonological awareness.“

- The Lexical Restructuring Model (LRM): From research conducted at the University of Florida: “According to LRM, as children’s vocabularies increase, children develop a more refined lexical representation of the sounds comprising those words, and in turn children become more sensitive to the detection of specific phonemes.”

According to the Lexical Restructuring Model, as very young children receive vocabulary through words heard, their ability to distinguish phonemes is refined because they begin to distinguish between words with minimal phonemic contrast: cat, caught, kit, cut, cute, coat, kite, Kate. The researchers explain:

If certain characteristics of words lead to lexical restructuring, structured vocabulary instruction could enhance children’s PA abilities. For example, teaching children words that are phonologically similar to one another and to words children know may cause those words to undergo restructuring so that they are kept distinct from each other in the lexicon. Targeted vocabulary instruction may heighten children’s sensitivity to the individual sound components that comprise words.

In an article examining the Lexical Restructuring Model, the authors conclude: “As children expand their vocabularies, underlying lexical representations must become more phonemically detailed to differentiate newly learned words from existing words in the lexicon.”

These three speech-related concepts seep into my speech-to-print instruction through an emphasis on encoding language as a lead-in to decoding it. For me, it simply means that I introduce a sound-spelling correspondence by using the sounds the student makes when speaking. Following the hear it, say it, write it, read it, use it sequence that Richard Gentry and Gene Ouellette recommended in Brain Words: How the Science of Reading Informs Teaching (which figures prominently in my instructional guide), I always introduce a new spelling pattern with word chains featuring minimal contrast so that each word shifts by just one phoneme, a feature of the Lexical Restructuring Model.

I was fortunate to have discovered Isabel Beck’s book Making Sense of Phonics right before teaching kindergarten, which provided me with lists of word chains for the common spelling variations. Since then, my lessons have evolved to complement these chains with my own chains derived from the words featured in the decodable text (adding words as necessary to avoid breaking the chain). This means students are practicing their phonemic awareness skills while priming their brains to recognize the new spelling pattern, which can take many exposures (especially for dyslexic children) in order to develop automatic word recognition.

Introducing the spelling patterns and words that will be practiced when reading decodable books by no means guarantees that these words spoken and written in isolation will be readily recognized and fluently read within the context of each story. (And, it should be noted, using decodable text does not preclude exposing students to other text types as well that have a mixture of spelling patterns.) I see examples of a lack of immediate transfer on a daily basis. This front-loading through word chains simply primes the phoneme-grapheme pump, in addition to introducing new vocabulary, without undermining the decoding practice to follow.

Therefore, practicing the target spelling pattern through encoding paves the way for decoding, but word recognition while reading the decodable books following dictation is not automatic by any means. Even after dictating word chains like can, cane, mane, man, tan, tap, tape, most of my students instinctively read the short a for most of the words the first time they attempt them. Accuracy accompanies practice. Moreover, they will read more than one decodable story and see the patterns learned interleaved in future stories introducing other patterns, so developing decoding skills is not diminished during speech-to-print instruction. This means:

- Students are getting child-directed speech through dictation, which provides foundational linguistic input that enables children to develop accurate phonemic representations and improve their vocabulary.

- Students are developing phonemic awareness skills through lexical restructuring as they actively discriminate between the sounds in the word chains they are writing, thereby restructuring these representations and making phonological distinctions through exposure to and expansion of vocabulary.

- Students are attempting their own spelling of a word–their invented spelling–before the correct spelling is revealed to them, further practicing and refining their phonemic awareness.

All this before my students see print on the board or in their decodable text: speech before print that can be particularly beneficial for my English Learners, who need to hear as much language as possible throughout the day.

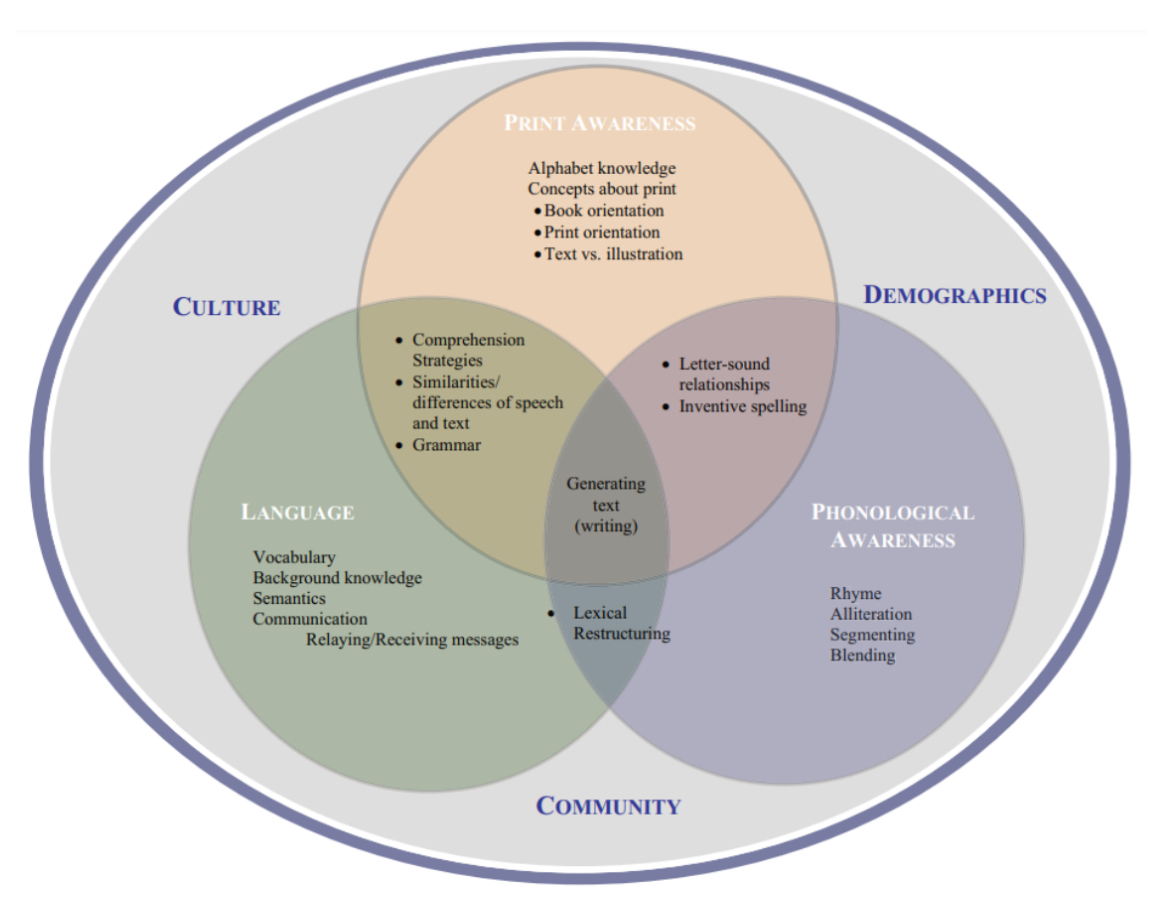

The Comprehensive Emergent Literacy Model: Early Literacy in Context

I’m including The Comprehensive Emergent Literacy Model not because I think it accurately depicts the relationship between literacy components (this is debatable), but simply because it’s the only model I’ve come across that includes lexical restructuring in addition to invented spelling and child directed speech (in the form of relaying/receiving messages in the Language section). One could argue that the absence of lexical restructuring in other models reflects insufficient research–which is fair enough. But its presence in this model reminds us of research we already have revealing that speech and print have a relationship that classroom practice can and should reflect to promote vocabulary growth and proficient reading. We sometimes forget that students with few literacy experiences in the home, as well as our English Learners, arrive in our classrooms in need of a comprehensive approach to reading instruction that compels us to employ instructional simultaneity, to integrate as many literacy components as possible to simultaneously remediate and accelerate reading performance.

A Phoneme Too Far

Criticism of the speech-to-print approach often focuses on instructional practices that cling to phoneme-grapheme connections for far too long, clutching on to those sound-spelling correspondences while failing to grasp the morpheme-spelling correspondences that are an important part of our morphophonemic language.

For example, linguist Lyn Stone expresses her concerns as follows: I’m haunted by the repeated telling children to ‘emphasise listening to each word and the sounds in each word prior to writing them’. This is fine up to simple CCVC/CVCC words . . . Speech-to-print is based on the faulty premise that ‘print is simply speech written down’.

Marshall Roberts expresses similar concerns, but he also poses this intriguing question on his blog on spelling rules, which he discusses on The Literacy View podcast.

Is it valid to sacrifice spelling competency to gain reading competency faster (there’s certainly an argument that reading opens more doors than spelling). Or could it be that sacrificing practising spelling rules to instead focus on increasing reading skill at a faster rate might actually ultimately pull spelling along with it due to implicit statistical learning?

Like Lyn Stone, he is concerned about what happens when spelling complexity increases as the Latin Layer (to borrow Diane McGuinness’s term) rears its hefty head, defying a speech-to-print solution for spelling and joining forces with all the other morphemes in longer words to negate the notion that spelling simply represents speech.

Pete Bowers laments that there is wide-spread reference to spelling-sound correspondences but not to spelling-meaning correspondences. Which leads me to pose this simple solution: Why can’t speech-to-print serve its purpose during beginning reading instruction and then yield to a more comprehensive approach to reading once two goals have been achieved: the alphabetic principle is established and students have had adequate practice segmenting and blending so that encoding and decoding are a done deal.

Perhaps what Lyn stone calls “the faulty premise that ‘print is simply speech written down’” is what Mark Seidenberg calls a convenient fiction, which echoes David Share’s explanation that “beginning readers of English are often (and wisely) first taught an oversimplified deterministic “rule” that the letter a (as in cat) makes the sound /æ/.” However, Lyn Stone warns that if we ask students to “listen to each word and sounds in each word prior to writing them as the major strategy after the basic GPCs are learned,” then we’ve got a problem.

To Tell the Truth

My primary consideration during beginning reading instruction is to focus student attention on the union of phonology, orthography, and semantics to promote orthographic mapping. As I manage the various activities in my beginning reading lessons–dictation of word chains and/or sentences (using either white boards or magnet tiles–or both), reading decodable text, and independent writing using invented spelling–I am always focusing on phonemes and how they are represented in print. In his foreword to Why Our Children Can’t Read and What We Can Do about It: A Scientific Revolution in Reading (Diane McGuinness, 1997), Steven Pinker says:

Children are wired for sound, but print is an optional accessory that must be painstakingly bolted on. This fact about human nature should be the starting point for any discussion of how to teach our children to read and write. We need to understand how the contraption called writing works, how the mind of the child works, how to get the two to mesh.”

We’ve already discussed how the mind of the child is “wired for sound” but what about meshing it with how the “contraption” called writing works? In a fascinating podcast discussion, Lyn Stone and Christopher Such explore in detail exactly how this writing contraption works as they drill down on the difference between encoding and spelling. They point out that while encoding is an important part of the writing process as children convert sounds to print, there’s a difference between encoding sound and spelling morphemes and words. Because spelling is harder than reading, once we leave the relative regularity of monosyllabic words, Lyn Stone reminds us that “not every letter sequence is a sound,” and she laments that “the actual spelling, not the encoding of sounds, is abandoned or not taught or left to chance.”

Here is how Kathy Rastle explains this important point that written language doesn’t simply reflect the representation of sound in her 2017 mid-career prize lecture, “Writing systems, reading, and language”:

If English writing were a perfect reflection of spoken language, the words herded, kicked, and snored might be spelled herdid, kickt, and snord, and the words magician and health might be spelled majishun and helth, losing the meaningful information that the English written forms convey. Thus, like the introduction of word spacing, these examples demonstrate how divergence from spoken language can be functional, by enhancing the transmission of meaningful information.

It’s clear, therefore, that while speech-to-print has tremendous utility at the beginning stages of reading as it anchors phonemes to graphemes, at some point, the stable spellings of morphemes dominate and take precedence over voiced phonemes, a distinction that needs to inform my instruction. Having spent the majority of my teaching time in elementary school with below-level first and second graders, this is a crucial point that I had not given enough serious thought, but one that I now carry with me into lessons I teach to all age groups of all abilities, taking into consideration the importance of sound-spelling correspondences as well as spelling-meaning correspondences. These considerations lead me to conclude that:

- Connecting sounds/letters/meaning facilitates reading and writing single-morpheme words through the process of orthographic mapping.

- Encoding phonemes facilitates decoding graphemes by practicing speech-to-print connections.

- Writing ‘action’ as ‘acshun’ encodes what I say through invented spelling but does not spell the word accurately.

- Knowing the suffix ‘tion’ (which is in fact ‘ion’) facilitates accurate spelling and provides access to understanding other words that end in that suffix.

- Connecting morphemes to meaning facilitates reading and writing multisyllabic words.

In “Following the Rules in an Unruly Writing System: The Cognitive Science of Learning to Read English” (2024), Devin Kearns and Cooper Borkenhagen caution us as follows: “Do not teach students a set of strategies that require extensive, high level conscious processing.”

But what, exactly, constitutes “high level conscious processing”? Of course, Lyn Stone is right that not every letter sequence is a sound, but in the beginning stages of reading instruction (and during all vocabulary instruction), we are guiding our students to pronounce words (as Linnea Ehri emphasizes) in order to map these words to memory, whether we are teaching can or can tank er ous. For students beyond the single-morpheme stage, we must emphasize, for example, that the suffix ‘ous’ sounds like ‘us’ but is not spelled that way (similar to other words with ‘ou’ pronounced /u/ like cousin, young, and touch), and we must also explain its meaning so that students can use this understanding to unlock many other words.

I want to teach whatever is easiest to help children to crack the code and allow statistical learning, set for variability, and self-teaching to kick in, even if this teaching misrepresents the writing system at this beginning stage as long as what I’m teaching does not compromise future learning. (This is a concern that Lyn Stone has expressed, for example, regarding whether ‘silent e’ should be called a split digraph).

While it is noble to consider ourselves the gatekeepers of linguistic truth, many of us simply do not have the luxury of teaching the truth if it “entails extensive, high level conscious processing.” Give me the quickest, most efficient way to help students crack the code (rather than teach the code as Mark Seidenberg warns us against) to get them into wide reading as soon as possible and allow statistical learning and self-teaching to have their sway.

Once students have cracked the alphabetic code, I can use their experiences with text to integrate other essential literacy components. As I guide my students through writing about what they read, I will be emphasizing true representations of the language (writing graphemes and morphemes rather than endlessly encoding speech), which entails accurate spelling through morphological awareness, proper syntax, and precise vocabulary–and their written pieces should reflect how well I’ve taught these components. And if they haven’t learned what I’ve taught, I reteach–rinse, repeat. As Anita Archer reminds us: I do–we do, we do, we do, we do–until you get it right when you do.

At the end of the Kearns and Borkenhagen article, they write:

At a mechanistic level, learning is not simply a process of acquiring the ‘rules’ of the writing system, though teaching students about reliable patterns is an important aspect of instruction. This model [Seidenberg’s triangle model] appears to overlap with the more widely known model of ‘orthographic mapping’, despite differences in the assumptions of how the learner acquires knowledge of rule-like patterns.

Going forward with my speech-to-print orientation, I will keep my lessons in line with these constraints by asking myself:

- What phrasing do I use to introduce graphemes that represent speech?

- When and how do I introduce morphemes to my developing readers?

- What are the instructional implications of distinguishing between encoding and spelling?

- How does the path to accurate reading differ from the path to accurate spelling?

Dealing with Decision-Making: Choices Matter

Drawing upon Steve Dykstra’s plea for professional decision-making, I end a piece I wrote about instructional uncertainty inspired by Emina McLean by saying:

We all need to face our collective faults related to overconfidence and find the professional humility necessary to frame uncertainty within the realm of the day-to-day practicalities of teaching, within the coalface consequences–to borrow Emina’s evocative phrase–of the choices we make. In short, we need to bestow upon ambiguity and inconclusiveness the deep respect they deserve.

I have a deep respect for the difficult decisions teachers make related to beginning reading instruction. I try to make my own decisions with humility and a nod to the reality that when reliable research is absent, I need to rely on other factors, including assembling routines that reflect my best understanding of the research as well as my understanding of the competencies I want my students to master. Yes, there is much uncertainty related to the benefits of speech-to-print over print-to-speech, but there is also promise in such an approach related to both effectiveness and efficiency.

We are imperfect purveyors of reading instruction, bombarded by reading recommendations and scrambling to sort through them in time to deliver a daily lesson. We are decision-makers through and through. How do you make yours?