Guest Blogger  Harriett Janetos, Reading Specialist

Harriett Janetos, Reading Specialist

Author, From Sound to Summary: Braiding the Reading Rope to Make Words Make Sense

When it comes to teaching foundational reading skills, sometimes ignorance really can be bliss. Determining which lessons in our basal-bloated teacher’s manuals merit instructional time and which do not is tedious, time-consuming, and too often unreliable when it comes to achieving student outcomes that justify the effort. Any time spent teaching the linguistic features of our language that do not have a direct application to learning to read goes too far beyond cognitive neuroscientist Mark Seidenberg’s practical advice regarding phonics instruction—get in, get out, move on—and must be tagged with a red flag. He is keenly aware that teachers should provide just enough instruction to give students escape velocity but no more than that. We overteach foundational skills at our peril, Seidenberg warns, because “the ‘harm’ of overteaching is the opportunity costs: It eats up precious classroom time that could have focused on other goals,” including time reading text representing a range of topics and genres. Three decades earlier, Harvard educational psychologist Jeanne Chall emphasized that “some teachers may inadvertently overdo the teaching of phonics.” The reason why we “inadvertently” overteach phonics is because we simply don’t have a reliable metric to gauge the usefulness of each linguistic component. And escape velocity, while a lovely metaphor, lets us down when it comes to lesson planning. But what exactly does it take to guarantee an effective escape?

As a reading specialist charged with maximizing remediation time with my students, positioning them to accelerate their progress toward reaching grade level proficiency, I don’t have a minute to spare overteaching phonics. Like Michael Pollan in his Eater’s Manifesto: Eat Food. Not Too Much. Mostly Plants, I adhere to a Teacher’s Manifesto: Teach Phonics. Not Too Much. Mostly Decontextualized. Once I accept this premise, the ironies start rolling in because my adherence to explicit, systematic phonics instruction decontextualized from literacy-rich lessons may be what separates me most from my Balanced Literacy colleagues, while a refusal to overteach phonics may be what bonds me to these same teachers but separates me from some of my Science of Reading counterparts. (For an informative infographic on contextualized vs. decontextualized skills, see Nathaniel Swain’s Teaching literacy the right way up: Inverting the balanced literacy playbook.)

For example, the reason why I have several sets of high quality decodable books in mint condition from the Reading First era two decades ago is because so many of my Balanced Literacy colleagues never used them. And while these books may not be authentic literature, I certainly consider them to be real books, ones that provide my students with authentic practice as I teach them their phonemes and graphemes, delighting when I hear them declare “I love that story!” as they so often do. But these decodables are just one of the many text types that my students have access to. We know that different books develop different literacy skills: decodables practice letter-sound connections and fluency; grade-level text promotes knowledge-building and comprehension; trade books provide language variety and motivation. As it turns out, focusing lesson routines centered on decodable text that facilitates phonics instruction can set up guardrails to prevent overteaching phonics. The question, therefore, of what to teach can be found in the decodable books themselves, leaving us to unite reliable instructional methods with high-quality materials.

The Transfer Paradox: A Tale of Two Texts

So let’s look at methods and materials. Carl Hendrick, author of How We Learn, emphasizes that the Transfer Paradox might possibly be “the most difficult challenge teachers face in instructional design . . . the deceptive trade-off between immediate performance vs. long-term transfer.” This is a good explanation for why we should not use predictable text during beginning reading instruction. The “immediate performance” that comes from memorizing a sentence pattern and then reading the picture rather than the word (I see a giraffe, a rhinoceros, a wooly mammoth, etc.) is offset by a failure to achieve “long-term transfer” due to the many missed opportunities to orthographically map spelling patterns and words in the text, a necessary step in the transfer process. This orthographic mapping is achieved through the act of decoding by linking letters to sounds. Hendrick explains that “what helps students perform well during initial learning may not prepare them well for applying that knowledge in different situations or problems they haven’t encountered before.”

By contrast, if we take orthographic mapping as our organizing principle for foundational skills, Linnea Ehri offers simple instructional guidelines related to fostering alphabetic knowledge through letter-embedded picture mnemonics (like Zoophonics) and teaching the segmenting and blending of words (encoding and decoding) with “plenty of practice reading text at an appropriate level of ease,” which is what a decodable book provides. Centering phonics instruction on decodable text offers an immediate reward for students that, unlike reading predictable text, is directly related to the reading process and the skills students need to become proficient. This reward reflects one of Carl Hendrick’s seven general principles of learning: how achievement leads to motivation. (The other six deal with memory capacity, meaning, novice vs. expert, remembering via forgetting, the difference between learning and performing, and knowing how to learn.) Translating this principle of motivation through achievement to practice means providing students opportunities to read words introduced through simple reading and writing activities that first target these words in isolation and then provide practice within a meaningful context.

The Science of Reading Meets the Science of Learning

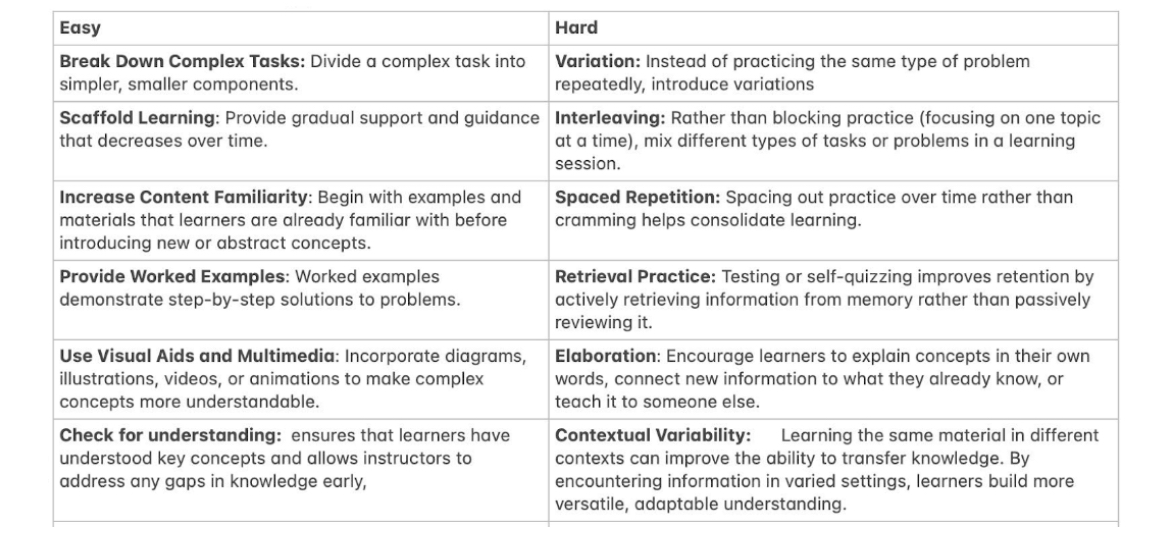

How, then, can we put this all together? How can we take the goal of facilitating orthographic mapping and combine it with Ehri’s instructional practices related to segmenting and blending, thus providing the necessary practice to implement the Goldilocks Principle: teaching just enough phonics, neither too much nor too little? (Note: the Goldilocks Principle is not one of the principles of the Science of Learning.) Carl Hendrick reminds us that learning happens when we combine making tasks easy with making them hard, so let’s see which of our activities accomplish the range of difficulty necessary to learn.

Make It Easy/Make It Hard

To make learning easy, we can break down complex tasks by introducing a new spelling pattern with word chains. This activity will scaffold learning by teaching students to access the spelling patterns within words through an emphasis on the minimal contrast between each word in the chain. We increase content familiarity by beginning with simple graphemes representing phonemes to establish the alphabetic code before introducing more complex graphemes. We can provide worked examples of encoding and decoding practices by demonstrating the step-by-step process of segmenting and blending as we model reading and writing. Use of Visual Aids such as single magnet tiles featuring one grapheme (ai, ea, igh, oa, ew, etc.) instead of one letter, along with high interest videos like Alphablocks—as well as other multimedia like blending and segmenting songs—make complex concepts more accessible. Lastly, daily use of whiteboards facilitates checking for understanding.

To make learning hard, we read decodable books that include both fiction and nonfiction pieces and a range of decodability that offers textual variation. Interleaving phonics instruction with phonemic awareness, vocabulary, and writing provides an essential integration of literacy components, while spaced repetition of the phonics patterns practiced over time consolidates the learning. Using white boards to actively retrieve information rather than passively reviewing it improves retention. We can elaborate by connecting known patterns and words to new words. Finally, if we teach a variety of text types depicting the variability within the range of decodable texts, students can self-teach by transferring existing knowledge to varied settings and “build more versatile, adaptable, understanding,” systematically developing their skills by applying them widely.

Nixing Nasalized ‘A’

The point is that if we are following these learning principles and prioritizing escape velocity to hasten time-in-text—time spent actually reading books—we don’t have a minute to spare teaching anything that derails or delays this goal. In general, making these choices isn’t easy, but we can derive some basic guidelines. For example, a colleague recently alerted me to a lesson in her phonics manual related to teaching nasalized ‘a’, how the /a/ sound changes in front of the letters ‘m’ and ‘n’. Although I’ve taught first graders for over two decades, this is not a term or concept I was familiar with. The following day, I taught a lesson to my first grade intervention students based on the story “A Cap for Pam” that allowed me to carefully observe my students as they used their sounding out skills first to segment and write and then to blend and read the words ‘can, cap, tap, Tam, Pam, Sam.’ I watched closely to see whether the nasalization confused them. As I expected, it didn’t, neither when dealing with the words individually nor when reading them in the story—just as it has never done over the past two decades! I consulted another colleague who said: “Why not just teach each ‘letter-sound’ in a one-size-fits-all way? When you see this letter/digraph, say ___. Any change in sound quality will then take care of itself in the blending process. The child will go on thinking that the /a/ in ‘ant’ is exactly the same as the /a/ in ‘apple’, but that’s a good fault.”

That ‘good fault’ is what Seidenberg calls a “convenient fiction.” Part of the unfortunate fallout from the Science of Reading movement is that we are often asked to teach too many inconvenient truths about our language which intrude upon time in text and language comprehension instruction. Mindful of Seidenberg’s caution related to opportunity costs, we know that teaching too much foundational knowledge takes time away from teaching world knowledge, in addition to time taken away from allowing students to actually read different kinds of books of varying lengths.

The Golden Mean

How do we efficiently and effectively prepare students for the literacy challenges ahead? In the lower grades, we have our wonderful read-alouds, so beautifully written and illustrated that my younger son’s first grade teacher would gently rub the cover while introducing each book, a loving massage to awaken the literary marvels within. The students listened in rapt attention, and eagerly asked and answered questions. We know that until students become proficient readers, knowledge-building through listening and discussing complex text is essential. Then we have our grade level text. Recently, I taught a first grade unit on how animals and plants grow and change, which had both fiction and non-fiction selections, displaying a range of decodability requiring a range of scaffolded lessons, and there are text sets related to the topic for subsequent student exploration. Finally, we have our decodable books which facilitate practicing phonics patterns within connected text so that word recognition is never a barrier to language comprehension.

Is it possible that one answer to overteaching the principles of the Science of Reading lies within the principles of the Science of Learning—along with the basic lesson that Goldilocks teaches us? Teaching high-needs students means teaching with an internal timer that tells us it’s time to move on and away from nice to know and toward need to know. Of course, making that determination isn’t always easy, but it may be easier than we might think. If both the little girl in the Three Bears and the grandmother in August: Osage County are right that the truth lives “where everything lives, somewhere in the middle,” then we must reject the extremes related to overteaching or underteaching phonics and just focus on what matters most when it comes to giving students the best chance of reaching escape velocity.

2 Comments. Leave new

Yes yes yes!!!!!!

Thank you for so eloquently putting into words what I’ve been saying and believe. 43 years as an educator, I’ve seen the pendulum swing several times. We need to find the middle and effective ways to teach with the pendulum in the middle!!!

I’ve only just noticed this! Thanks for reading and responding—I’m so glad you agree based on your many years of teaching.